I told my teenager I was writing a post called "The Power of Vulnerability" and asked what I should include. They said, "Tell them to be careful!"

My kid reads a lot of new and young writers online. Much of what they read has emotional vulnerability and spark, but it can tend toward trauma dump rather than story. Emotion and vulnerability without shape can be therapeutic, but it’s often at the cost of reaching readers.

According to my astute teenager, vulnerability is very powerful, so be careful how you wield it.

Social researcher Brené Brown defines vulnerability as “uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure.” She argues that it is one of the most important tools to enable us to connect to other human beings. But, she writes, “It's not oversharing, it's not purging, it's not indiscriminate disclosure, and it's not celebrity-style social media information dumps. Vulnerability is about sharing our feelings and our experiences with people who have earned the right to hear them.” Part of our implied contract with a reader is that we will tell a story. Studying craft can teach you the tools to add shape to the emotional content of your stories.

With that in mind, let’s look at a few ways you can harness the power of vulnerability in your writing.

Make Your Characters Vulnerable

While writerly vulnerability needs to be well placed, making your characters situationally vulnerable can encourage readers to empathize with them.

Harry Potter is an orphan, unloved by his aunt and uncle who serve as his guardians. He is alone–vulnerable.

Katniss Everdeen is from the poorest district and worried about how to feed her family. When her sister is called as a tribute, that potential loss makes her even more vulnerable as she would risk everything to keep her sister safe. Then she is thrown into training for the Hunger Games, where she will be exposed to the elements and surrounded by enemies and traps. Each movement toward increased vulnerability heightens the stakes and tension.

A character’s emotional vulnerability may take time to reveal over the course of the story. Starting with their worst experience or the worst thing about them can backfire. In an early draft of an in-progress middle grade novel, I led with one of my character’s worst secret feelings, one she wouldn’t have said out loud to anyone. An award-winning author gave me feedback and said, on third line, “Oh, goodness. I already don’t like her very much.” I had led with her emotional vulnerability–showing the worst first–instead of leaving that deep layer until readers knew and loved my character.

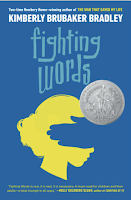

In contrast, Kimberly Brubaker Bradley’s FIGHTING WORDS is a stellar example of the narrator walking the reader toward facing the most difficult situation. The narrator and her sister are more than their trauma, and we get to know them as three-dimensional people before we understand the full extent of what they’ve been through.

Remember the Range and Scope of Vulnerability

Vulnerability is not limited to trauma or dark feelings. It can be vulnerable to share what brings you joy, or to nerd out about an arcane subject you find fascinating. All of those parts of you are available to use in your work. Parceling them out in little bits can make your stories richer.

Author Lindsay Lackey used this trick to develop the character of Wanda in her middle grade novel All the Impossible Things, the story of Red, a girl in foster care. Wanda, Red’s mother, is unstable, has a drug addiction, has spent time in jail, and makes Red promises she can’t keep. In early drafts, Wanda wasn’t very likable, and Lindsay’s critique partners had trouble connecting with the character. Lindsay had trouble writing the character. So she used a favorite memory from her own childhood and gave that experience to Wanda. It opened up the character and made Lindsay and her readers more able to relate to her. (Lindsay speaks about this in a presentation she offers called Building a Book with Touchstone Moments.)

Balance your Vulnerability as an Artist

Many writers find themselves with the opposite of Lindsay’s challenge–they find too much of themselves in a character. It can be essential to your writerly health to separate yourself from your characters–to let them be their own people, rather than a mirror of you.

In her writing memoir Thunder and Lightning, writing guru Natalie Goldberg talks about the moment her main character, who was based on herself, became her own person: “I made believe I was Nell telling Nell’s story. And then one day, lo and behold! . . . as I wrote, Natalie faded out. She was gone, disappeared, and this character Nell Schwartz was telling her own story through my hand. . . Even now I can remember the sensation of feeling unglued–I experienced a heady freedom. I no longer existed. I could lay down my burden and let the kid walk on her own two feet.”

Keeping your characters too close to your own experience, personality, and quirks has a couple of pitfalls: it can make your characters flat, if you take out all your negative qualities, or can stifle the action, if you’re too protective of your character, and it opens you up as a writer to a particular kind of vulnerability. It becomes difficult to take feedback constructively when you are your writing.

Vulnerability is Powerful

It is the nature of being an artist to be vulnerable–to open ourselves to risk as we show our art to others.

Brené Brown says, “To put our art, our writing, our photography, our ideas out into the world with no assurance of acceptance or appreciation—that’s also vulnerability.”

Yes, the act of writing and sharing our work is a risk. But there is great reward in this kind of vulnerability, because it connects us to others and allows our readers to connect with our characters, feel with them, and grow with them.

Anne-Marie Strohman writes stories for children of all ages, from picture books to YA. She holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She has presented at SCBWI events in multiple regions, and she founded, co-edits, and writes for the blog KidLit Craft (kidlitcraft.com). She’s the current Scholar-in-Residence for the SCBWI San Francisco/South region.

You can read more of her essays in the KidLit Craft monthly newsletter.

1 comment:

Best post on vulnerability in writing that I've read! Thank you!

Post a Comment