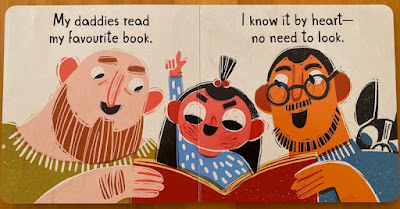

In her coverage for School Library Journal of the most recent Bologna Book Fair, Betsy Bird observed a general lack of titles with visible LGBT content from or in other languages, with the exception of my two rainbow family board books illustrated by Elīna Brasliņa, Bedtime, Not Playtime! and Early One Morning, published by Orca in English & French for the US & Canada (and in 35 other languages around the world):

While there has certainly been an increase of titles being published in the English speaking world in recent years, even if focused more heavily on titles for older readers (middle grade and YA) which are not always as immediately visible on stands at the bookfairs, I think that part of the problem behind the absence Betsy noted is economic: a lot of the independent publishers around the world who are indeed publishing these titles are either not attending the fair and/or do not have a stand of their own, thus making discoverability part of the problem.

For instance, at Bologna were the two women behind a nascent publishing project in Cyprus to focus on gender positive children's books, FylAnagnosia, who are still in the fundraising stage. But of course, it is too early for any of their homegrown titles or the translations they plan to publish to be present at the fair, and it is much harder for people who are both "floating" to encounter one another than it is to wander by and browse the titles displayed at a stand with its physical presence.

Betsy's observation, though, made me go back to my own bookshelves, because historically, many of the early picture books with LGBTQ content that were published in the US were in fact translations. (And my own board books were originally written & published in Spanish, so the English editions are later self-translations.)

The very first LGBT picture book that I know if is Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin written by Susanne Bösche, with photos by Andreas Hansen, published in Denmark in 1981, and published by the Gay Men's Press in 1983 in a translation by Louis Mackay. (GMP was a UK publisher with US distribution.)

And the well-known delightful (if frequently banned or challenged) picture book King & King by Linda de Haan and Stern Nijland was originally published in 2000 in the Netherlands, before being released in English by Tricycle in 2002.

So a translation definitely paved the way before groundbreaking (but still quite controversial) domestic picture books like Lesléa Newman's Heather Has Two Mommies (1989) and Michael Willhoite's Daddy's Roommate (1990) were published, both from independent LGBT press Alyson Books. (It would be many years still before titles with LGBT content were regularly published by mainstream, commercial presses.) And another translation made waves for inverting traditional fairy tale gender roles (and for its depiction of the first same-sex kiss in a children's picture book).

So while English language books with LGBT content might be more visible these days, it is to no small degree thanks to translated titles that led the way.

I'll conclude with a sampler of picture books in other languages from my personal library:

Citlalli tiene tres abuelas written by Silvia Susana Jácome and illustrated by Medusczka is a story about a trans grandparent, published in Mexico in 2017 by the Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación and distributed free.

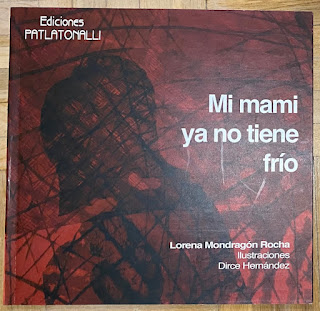

Also from Mexico are the titles from Ediciones Patlatonalli, a collective that produces picture books featuring lesbian mothers, such as Tengo una tía que no es monjita written by Melissa Cardoza and illustrated by Margarita Sada Romero (2004) or Mi mama ya no tiene frío written by Lorena Modnragón Rocha, illustrated by Dirce Hernández (2011).

From Uruguay, El vestido de Mamá written by Dani Umpi and illustrated by Rodrigo Moraes, published by Criatura Editora in 2011 is a charming story about a young boy who likes to wear his mother's green sequined dress, and questions why we wear different kinds of clothing in different situations (bathing suits, winter coats) and why these have to be restricted by gender.

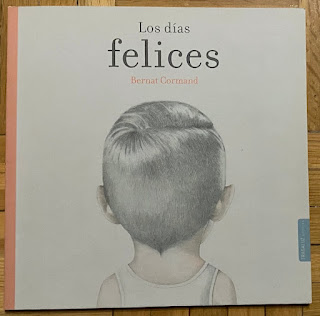

Los días felices written and illustrated by Catalan author/illustrator Bernt Cormand is a poetic story about first love between two young boys until one of them goes away when his family moves, published in 2018 by Tragaluz in Colombia and A Buen Paso in Spain.

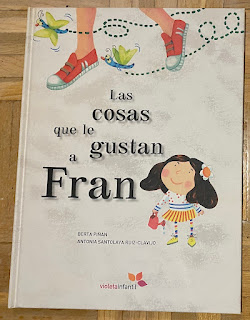

Las cosas que le gustan a Fran written by Berta Piñán and illustrated by Antonia Santolaya Ruiz-Clavijo is a story about a young girl and all the things that Fran (her mother's girlfriend) likes, which was published in a bilingual (Spanish/English) edition by Hotel Papel in 2007.

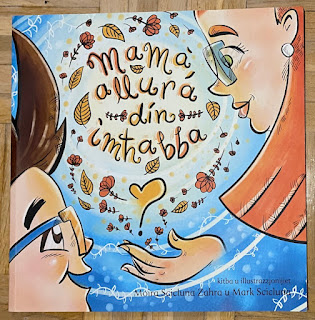

And to not be monolingual, even if (since Spanish is one of my primary languages for both creating & translating) let me conclude with a picture book from Malta about a boy with two mothers: Mamà, allura din imħabba? written by Moira Scicluna Zahra and illustrated by Mark Scicluna, published by Merlin Publishers in 2017.

* * *

Lawrence Schimel is a bilingual (Spanish/English) author & anthologist who has published over 120 books in many different genres. He won a Crystal Kite Award for his picture book Will You Read a Book With Me?, illustrated by Thiago Lopes, and his books have also been chosen for the White Ravens and by IBBY for Outstanding Books for Children with Disabilities (three times). His children's books featuring rainbow families, Early One Morning and Bedtime, Not Playtime!, both illustrated by Elina Braslina, have been published in 46 editions in 37 languages, including Romansch, Welsh, Icelandic, Changana, isiZulu, and Luxembourgish. He is also a prolific literary translator, both into Spanish and into English, of more than 130 books. He lives in Madrid, Spain, where he founded the SCBWI Spain chapter and served as RA for the first 5 years.